How Did We Get Here?

The Gospel of Winning: From Victory to Narcissism

Winning, Safety, and the Gospel’s Reversal

As a pathologist, I was taught that using low power on the microscope is evidence of a high-power brain. At high magnification, everything can be interpreted as malignant. Cells may seem awry, tissue ruptured, the sharp evidence of disease leaping out from the slide. Taken out of context, what is simply reactive or inflamed can be mistaken for deadly pathology. And when that happens, treatment itself can do harm: The surgeon’s knife can cut away what was never cancer, oncologic poisons strike what was never fatal. A false diagnosis can do tremendous harm.

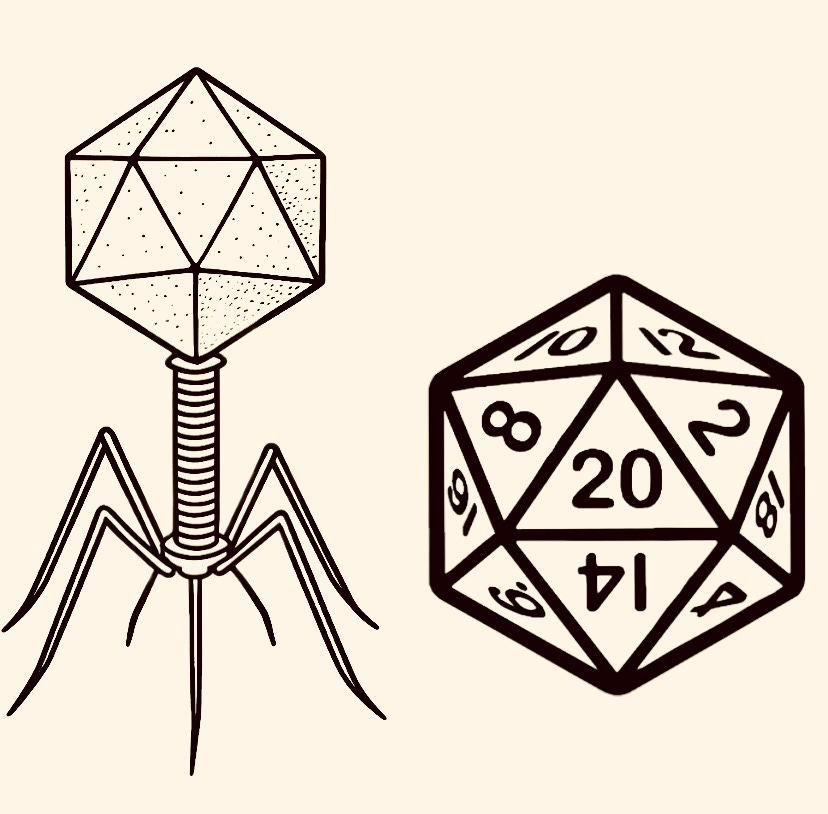

But my training carried me deeper still. Earlier in my career I was an electron microscopist, I peered at the edge of life magnified a hundred thousand times.

The perfect icosahedral head of a bacteriophage, a twenty-sided form that uncannily resembled the dice I rolled in the late 1970s playing Dungeons & Dragons.

Back then, Tolkien gave us the framework for our characters, Led Zeppelin provided the soundtrack, and those dice in my hand echoed the same geometry I would one day study under the lens of science.

Through using the microscope with excellent mentors, I also learned restraint. You cannot live only at high power. Pull back to low power, and a single cell becomes part of a larger pattern. It is essential to know what is healthy or distorted at low magnification and understand before charging ahead to high mag. This is one of the greatest obstacles to trainees.

It seems that in everything the capacity to use power appropriately highlights the essential attribute of wisdom.

Our capacity to draw even further back to the pilot’s horizon or the astronaut’s window, allows whole continents to come into view:

Rivers winding like arteries

Currents moving like breath

Cities shining like constellations

It is at that scale… low power, 30,000 feet, even orbital altitude — that the deeper question emerges: How did this happen? What story explains what I’m seeing?

That is the same question I find myself asking about our culture today. At high power, many things look malignant:

Families fractured

Neighbors suspicious of one another

Half the nation pitted against the other half

Accusations fly in every direction :

“Racist, narcissist, toxic, patriarchal, elitist.”

But when we pull back from the noise, something larger comes into view. Patterns begin to emerge, and with them, the story that brought us here.

Drunk on Winning

Some of the roots may reach back to World War II. America came out of the war intoxicated with victory. We had won. We had “saved the world.”

That became our story, anchored in pride, nuance was lost: the complexity of alliances, the enormous sacrifice of others, and the unspeakable cost in human suffering faded behind a single narrative: we are the good guys, and we won.

Poland lost six million people—nearly a fifth of its entire population. The Soviet Union endured more than twenty-seven million deaths, almost a quarter of its people. China’s losses ran into the tens of millions, through both combat and famine. The United States, though deeply scarred, lost less than one percent of its population. Remembering these contrasts keeps us from reducing World War II to a single storyline of triumph, and reminds us that for many nations the war was not a victory parade but a season of survival through devastation.

Winning moved from being a result to an identity. Over the decades it hardened into habit: being right, being strong, being first became the American gospel.

The Fairness Doctrine Falls

By 1987, when the FCC repealed the Fairness Doctrine, the country was already primed. For nearly forty years, broadcasters had been required to give airtime to opposing viewpoints on controversial issues. It wasn’t perfect, but it forced a measure of dialogue. If you heard one side, you were at least exposed to the other.

In the mid-1980s, President Ronald Reagan’s FCC — led by Chairman Dennis Patrick — argued that the rule was outdated. With cable and new stations multiplying, they claimed government no longer needed to enforce balance. In August 1987, Patrick and the FCC voted to repeal it. When Congress later tried to reinstate the rule, Reagan vetoed the bill.

With the doctrine gone, so was restraint. Media no longer had to hold tension between perspectives; it could take a side and amplify it. Partisan voices grew louder, talk radio exploded, and the cultural reflex of us vs. them finally had a microphone.

Echo chambers flourished. Winning replaced listening.

Safety Redefined

Meanwhile, another cultural shift was unfolding. Through the 1970s and 80s, legal precedents in the insurance and liability industries redefined what “safety” meant.

What had once been ordinary risk — accidents, injuries, loss — became legal exposure. In Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Co. (1978), the jury’s $127 million verdict over the Pinto’s exploding gas tank shocked corporate America. The growing wave of asbestos litigation in the same era brought settlements in the hundreds of millions, while medical malpractice suits saw jury awards climb from thousands into millions.

Each of these verdicts signaled that safety was no longer about resilience or recovery, but about shielding against financial ruin. Insurance companies adjusted with soaring premiums, narrowed coverage, and a whole industry reoriented itself toward one goal: minimizing exposure. Corporations responded by padding themselves with disclaimers, warning labels, and fine print.

Families learned to guard against blame. The people next door were no longer allies to lean on, but potential liabilities to guard against.

Children raised in this environment came to believe that the deepest wound was not the injury itself, but the exposure… not the pain, but the blame.

Parents followed suit, hovering like helicopters or flattening obstacles like steamrollers, treating their children as extensions of their own winning egos.

Safety was no longer community or resilience but insulation and boundaries.

The Moral Majority

Religious life mirrored the pattern. In the late 1970s and 80s, the Moral Majority rose in response to cultural upheavals. Founded in 1979 by Baptist pastor Jerry Falwell, it quickly became the flagship of the Religious Right. With millions of members and chapters across the country, it urged evangelicals to mobilize politically in defense of what it called “family values.”

Its causes included opposition to abortion, resistance to the sexual revolution, and a defense of traditional family and prayer in schools. Politicians courted it, presidents listened to it, and within a few short years it had turned evangelicals into one of the most reliable voting blocs in America.

But the cultural reflex underneath was the same: evangelicals felt besieged and circled the wagons.

The result was a religious version of the same survival instinct:

Isolation from science and education

Suspicion of mainstream media

A siege mentality that defined safety not as trust in God, but as protection from “the world”

The church was discipled into the same tribalism as the culture.

Instead of being salt and light, we built bunkers. Rather than engaging with humility, we mirrored the us-and-them reflex. Winning became the measure of faithfulness.

James C. Dobson and His Legacy

James C. Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family, was one of the most influential evangelical leaders of the late 20th century. His voice reached millions through books and broadcasts, offering practical guidance on parenting, marriage, and faith. Many households found strength in his counsel, and his commitment to nurturing family life left a deep imprint on a generation.

At the same time, Dobson’s reach grew far beyond pastoral advice. His message became a rallying cry in the political arena, shaping not only how families lived but how evangelicals engaged in public life. With conviction, he called believers to defend truth in the cultural battles of his day, and in doing so he helped link Christian identity with political allegiance.

That shift carried both power and peril. Under his influence and others like him, faith increasingly bore political markers:

The family defined not only as biblical order, but as a political badge.

The enemy not just sin, but unfortunately the neighbor across the aisle.

The test of faith not only devotion to Christ, but loyalty to the cause.

Dobson’s legacy is therefore complex. He strengthened homes and inspired parents to raise children with conviction, yet he also helped set patterns that discipled the church into a partisan identity. To reflect on his life is to hold both realities together: the encouragement of his vision for family and the entanglement of that vision with the culture wars that continue to shape us.

The Training Grounds

This survival reflex was reinforced by everyday practices.

Board games are not wrong, but they train us to divide into sides and prize victory.

Sports are not evil, but they feed tribal instincts of “my team vs. your team.”

Branding is not inherently false, but it teaches belonging by exclusion.

Individually harmless, together they nurtured an inner reflex that could be easily manipulated: the need to win, the instinct to insulate, the suspicion of anyone on the other side.

Rome had perfected this same training on an imperial scale. The arena channeled tribal passion into loyalty to gladiators and chariots instead of resistance to empire. The marketplace tied every transaction to Caesar’s image, teaching that survival depended on allegiance. The media of power — decrees, monuments, and arches — kept the story always the same: Rome is eternal, Caesar divine.

Our modern practices echo theirs. What Rome imposed by spectacle, commerce, and propaganda, we rehearse in games, sports, and brands. Small habits that feel innocent can become the soil where larger idols take root.

The Age of Narcissism

Today, the most common insult is “narcissist.” Families collapse under the accusation, friendships dissolve, churches fracture, communities unravel.

But the word has shifted. It no longer points to a rare disorder; it has become shorthand for unsafe.

“The true engine of narcissism is not vanity in the mirror, but fear in the heart.”

Beneath the label is something deeper: our culture has been discipled by winning and safety.

Winning: worth measured by triumph.

Safety: shame covered at all costs.

If I win, I won’t be humiliated. If I protect myself, I won’t be exposed.

And the enemy of God has exploited this. He does not need to silence us if he can turn us against each other.

This fracture is the exact opposite of what God blesses and what Christ prayed for:

“How good and pleasant it is when God’s people live together in unity! It is like precious oil poured on the head, running down on the beard, running down on Aaron’s beard, down on the collar of his robe. It is as if the dew of Hermon were falling on Mount Zion. For there the Lord bestows his blessing, even life forevermore.”

— Psalm 133“My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

— John 17:20–21

Parables that Expose Us

Jesus’ parables were never polite illustrations; they were scalpels. Each one cuts into the human reflex to secure ourselves — either by winning or by insulating — and exposes how hollow those strategies really are.

The Pharisee and the Tax Collector (Luke 18:9–14)

The Pharisee “wins” the moral game. He stacks up virtue like points on a scoreboard: fasting, tithing, moral superiority. His confidence is in his performance, which shields him from shame. The tax collector does the opposite. He unmasks himself, names his need, and asks for mercy. And Jesus shocks His hearers: the one who exposed his shame went home justified, while the one who covered it did not. In a culture like ours—obsessed with projecting success and labeling others unsafe—Jesus says the only way home is through vulnerability.

The Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37)

The lawyer asks, “Who is my neighbor?” It sounds innocent, but beneath it is a survival question: Where can I draw the line that keeps me safe? Who am I obligated to, and who can I exclude? Jesus obliterates the line. The hated Samaritan is the true neighbor. The categories collapse: safety cannot be defined by who is in and who is out. In a world addicted to identity politics and culture-war maps, this parable dismantles our borders and leaves us only one command: go and do likewise.

The Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32)

Both sons are playing the same survival game. The younger son grasps at life by demanding his inheritance, trying to win freedom on his own terms. The elder son plays the opposite hand: he stays, obeys, and uses scorekeeping as leverage. Both are insulated—one from humility, the other from joy. The father shatters both illusions. He runs to the prodigal with mercy, and he pleads with the elder with tenderness. Love does not reward winning or losing; it restores the family

The Rich Fool (Luke 12:13–21)

Here, safety is revealed as illusion. The man builds bigger barns, insulating himself against uncertainty. He believes he has mastered tomorrow—until God calls his soul that very night. His insulation was not protection but distraction. How modern this sounds: bank accounts padded, homes alarmed, reputations curated, and yet one diagnosis, one phone call, one breath is enough to collapse the illusion.

The parables expose the way we play the same games:

Winning the moral contest

Drawing lines to keep safe

Grasping or scorekeeping

Stockpiling for protection

Even in the legacy of leaders like James Dobson, whom we rightly honor, these echoes and reflexes manifest. The correct desire to support families can at times mirror the Pharisee’s confidence in moral winning or the Rich Fool’s instinct to insulate.

We must be vigilant as we are reminded that even our most trusted guides are not exempt. Only Christ breaks the cycle.

What Scripture Really Says About Winning: The Bible speaks of crowns, races, and victories — but not as we do.

“Peace I leave with you; My peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give to you. Let not your hearts be troubled, neither let them be afraid.” John 14:27

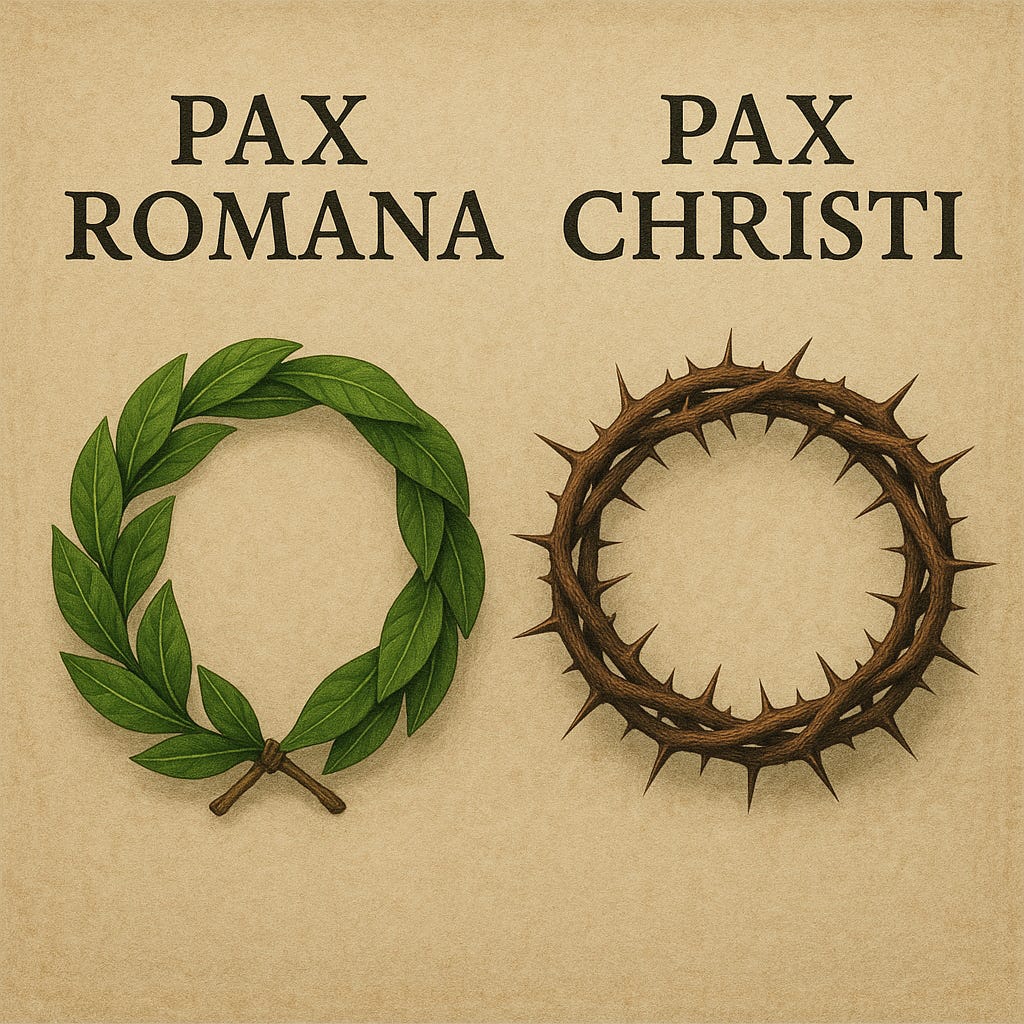

The Roman Empire recognized that the best way to control the populace was through three arenas of power.

The marketplace — the agora, where every transaction was stamped with Caesar’s image, every coin carried his name, and trade itself testified to Rome’s authority.

The spectacle of sport — amphitheaters, circuses, and gladiatorial games, where “bread and circuses” (panem et circenses) pacified the masses. Loyalty to your chariot team or gladiator house became a substitute for civic unity.

The media of power — imperial decrees read aloud in public squares, arches and monuments carved with Caesar’s victories, coins and statues proclaiming that Rome was eternal and Caesar divine.

Rome trained its citizens to believe survival meant allegiance, entertainment was the channel for passion and distraction, and truth was whatever the empire proclaimed.

Paul stepped directly into that world. He used the same imagery of the stadium and the crown….not as endorsement but subversion to show the new gentile believers another way.

Where Rome exalted winners, Paul showed that true victory was endurance in faith. Rome crowned athletes with a laurel that withered….. but Paul spoke of a crown of glory that never fades. Paul preached the cross opposing Rome’s penchant for filling its arenas with spectacle.

In the cosmic spectacle, the very place of apparent defeat became the revelation of the deepest love.

“Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one gets the prize? Run in such a way as to get the prize. Everyone who competes in the games goes into strict training. They do it to get a crown that will not last, but we do it to get a crown that will last forever.”— 1 Corinthians 9:24–25

“Therefore I do not run like someone running aimlessly; I do not fight like a boxer beating the air. No, I strike a blow to my body and make it my slave so that after I have preached to others, I myself will not be disqualified for the prize.”— 1 Corinthians 9:26–27

“But one thing I do: Forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus.”— Philippians 3:13–14

“Similarly, anyone who competes as an athlete does not receive the victor’s crown except by competing according to the rules.”— 2 Timothy 2:5

“I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Now there is in store for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, will award to me on that day.”— 2 Timothy 4:7–8

For Rome, the prize honored was Caesar….his wreath, favor, and empire.

Paul disciples us to strive for an entirely different prize: to know Christ and to share in His sufferings.

“I want to know Christ — yes, to know the power of His resurrection and participation in His sufferings, becoming like Him in His death… I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus.”— Philippians 3:10,14

Peter and John echo the same truth:

“And when the Chief Shepherd appears, you will receive the crown of glory that will never fade away.”— 1 Peter 5:4

“Be faithful, even to the point of death, and I will give you life as your victor’s crown.”— Revelation 2:10

And at the center is the hymn of Philippians 2 a scripture that all should commit to memory:

“Though He was in the form of God, He did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but emptied Himself… He humbled Himself, becoming obedient to death — even death on a cross. Therefore God exalted Him to the highest place and gave Him the name that is above every name.”

In the kingdom of God, winning means laying down your life.

The Cross: The Reversal of Winning and Safety

All of Scripture converges here. The metaphors of crowns and races, the calls to humility and endurance are not abstractions. They all lead us to one place: the cross.

If our culture has discipled us in winning and safety, God overturned those idols in the most unexpected way. He did not send His Son to seize victory by force or to shield Him from suffering. Instead, He gave Him up. And Jesus, in love, offered Himself.

This was not in triumph or insulation, but in the most unsafe and excruciating act of love the world has ever seen.

To human eyes, it looked like failure: mocked, stripped, crucified outside the city gates. To human instinct, it looked like exposure: vulnerable, shamed, unsafe. Yet here God’s love and power were revealed most fully.

“But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.”— Romans 5:8

“For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”— 1 Corinthians 1:18

“Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.”

— 1 Corinthians 1:22–24“This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us. And we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers and sisters.”

— 1 John 3:16

From the beginning, humans tried to hide their shame…

“they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves” (Genesis 3:7)

But at the cross, Christ bore the opposite: stripped naked, exposed, and shamed. He endured it not for Himself but for us….

“for the joy set before Him” (Hebrews 12:2)

Psalm 22, which begins with desolation — “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” — ends with triumph: “They will proclaim His righteousness, declaring to a people yet unborn:

He has done it!” (Psalm 22:31). On His lips, that became: “It is finished.” (John 19:30).

The cross shows us that Jesus’ mission was never about winning as the world defines it. It was to serve, to lay down His life, to bear our shame, and to open joy on the other side of loss. What Adam hid, Christ exposed. What Rome mocked, God exalted. What looked like defeat became the greatest victory of love.

In Christ, victory is found in surrender. Safety is found in exposure. Love is found in a cross.

The Pathologist’s View

Zoom in: the pathology is clear — division, suspicion, shame, fracture.

Zoom out: the trajectory is just as clear — triumphalism, the fall of fairness, the redefinition of safety, the training grounds of tribalism, the retreat of the church, the dominance of money, the rise of suspicion.

But the gospel diagnoses and heals differently……

Where We Go From Here

If the mandate is love, then the obsession with winning and the idol of safety must die.

Love does not divide the table into sides — it makes the table bigger.

The question is not only how did we get here?

The deeper question is: where do we go now?

And the answer is the same as it has always been:

Love your neighbor as yourself. (Mark 12:31)

Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you. (Matthew 5:44)

Lose your life, and you will find it. (Matthew 16:25)

For this is the way of Christ, who…

“for the joy set before Him endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God.” (Hebrews 12:2)

And when the work was finished, His final word was not defeat but victory:

“It is finished.” (John 19:30) — or as the psalmist foresaw, “He has done it.” (Psalm 22:31)

This is the gospel’s reversal: what looked like loss has become everlasting triumph. Love has overcome.