From Berlin to Bethlehem to Brazil

An Advent Reflection on the Body God Chose

An Advent Reflection

In the fall of 2016, I sat inside Maracanã Stadium during the Paralympic opening ceremony. A thin mist softened the light across the arena. The athlete chosen to ignite the cauldron moved slowly up a rain-covered ramp in his wheelchair. The stadium fell silent as he climbed. When the flame rose, something settled over the crowd — a recognition that dignity is not performance. I felt the weight of it before I could explain it. The moment said something true about what it means to be human.

The man carrying the flame was Clodoaldo Silva, one of Brazil’s most accomplished Paralympians. His presence changed the meaning of the ceremony. A ritual first created in 1936 to project mastery, uniformity, and physical perfection had been placed in the hands of someone whose life testified to endurance rather than advantage. The contrast revealed something deeper than words could hold.

Only later did I understand why it stayed with me.

When I replayed the scene, I noticed something I had missed in the moment. As Clodoaldo climbed, the rain made the ramp slick, and his wheels slipped. He tipped backward before steadying himself and continuing upward to light the flame. The stadium held its breath, but what followed was not embarrassment. It was recognition.

That image lingered for reasons I couldn’t name at the time. It quietly echoed a deeper story — One who also stumbled under the weight of what He carried, and yet kept moving toward the place where love would be ignited for the world.

I’m not collapsing the two stories. One is the center of redemption; the other simply reminded me of it. But the pattern was unmistakable: light carried through vulnerability, not spectacle. Strength revealed through a body that knows weakness.

Berlin and What Came Before

Eighty years earlier, in 1936, the modern Olympic ceremony had been created for an entirely different purpose. The torch relay and the opening spectacle were designed in Berlin as propaganda for Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. Every element was arranged to display a purified ideal of humanity—controlled bodies, rigid symmetry, and a myth of superiority. Any sign of limitation was removed.

Leni Riefenstahl shaped much of that visual language. Her Olympic films and choreography turned the human body into a symbol of purity and dominance. Through engineered camera angles and staged processions, she presented an image drawn from Nietzsche’s vision of the Übermensch—strong, autonomous, flawless, and free from anything that suggested weakness. What appeared elevated on screen depended on something far darker beneath it: the removal and erasure of those who did not fit the ideal. The weak were hidden, sterilized, or eliminated so the myth could stand.

This was not new. That framework echoed an older world.

The Greek Ideal

Long before Rome or Berlin, the Greek world shaped the imagination of the West through its hero stories and its sculptures. The body itself became a declaration — balanced, strong, and unmarred. Statues of warriors and gods set an expectation of what a valuable human should look like. The heroic ideal carried the belief that worth is shown through strength and the absence of weakness. Rome absorbed that vision, and it lived beneath the surface of later cultures, including the one that shaped the 1936 Games.

That impulse, the longing for a humanity above the human, a life lifted out of limitation……. underlies some of the earliest confusions in Scripture as well. The line in Genesis about the “heroes of old, the men of renown” is often mistranslated or misunderstood as describing supernatural hybrids. But the Hebrew text does not require that reading. It refers to powerful human figures who had fallen from their vocation — violent strongmen elevated by reputation and feared by their neighbors. The ancient world tried to explain such people through myth: demigods, hybrid beings, half-divine warriors. Scripture does the opposite. It brings the story back down to earth. These were not divine creatures crossing boundaries but human beings exalting themselves beyond their calling.

This same confusion prepared the ground for later distortions. By the time Christianity spread into the Greek-speaking world, the heroic ideal and its surrounding myths had already shaped how people imagined transcendence. Gnosticism took root in that soil. Its teachers claimed that matter was inferior or corrupt, that the physical universe was a mistake, and that salvation meant escaping the body. In that system, weakness and flesh were considered defects, not places where God could dwell.

A worldview that rejects the body always moves toward either mythmaking or contempt. It imagines humanity without vulnerability, spirit without flesh, strength without limits. Rome carried this forward, and centuries later the Third Reich revived the same impulse with technological precision.

Rome and the Third Reich

In the Roman Empire, the vulnerable were not protected. Infants who were unwanted, ill, or disabled were often abandoned outdoors. Ancient writers referred to this as exposure. Life was measured by strength, utility, and order. Those who did not fit the ideal were quietly erased.

The Third Reich revived this same impulse on a far more destructive scale. Both systems used public ritual to declare who mattered.

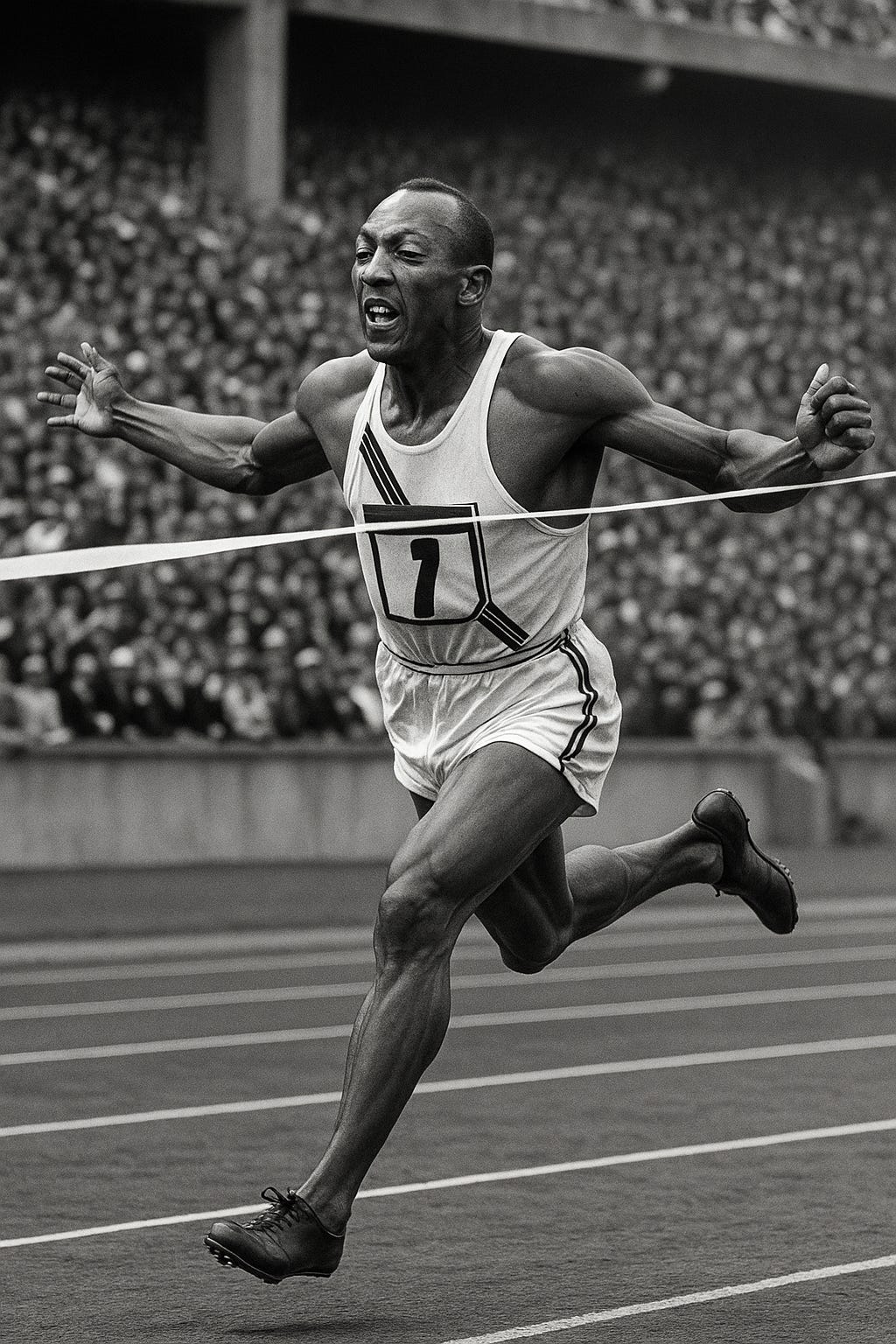

Yet even in the 1936 Games, truth appeared unexpectedly. Jesse Owens — the young American from Ohio State, where I trained years later — stepped onto the track and quietly contradicted the ideology around him simply by running with integrity. His presence revealed what the spectacle attempted to hide.

I carried that contrast with me as I sat in Rio in 2016. A ceremony first shaped by the imagination of the Third Reich was now being carried forward by someone whose life embodied a very different kind of courage. The contrast illuminated something larger than that single night.

Advent brings this into focus.

The World Christ Entered

Jesus was born into a society shaped by the same instincts that governed both Rome and later Berlin. Fragility was not something those cultures valued. It was often pushed aside. Luke describes His birth with striking simplicity:

“She gave birth to her firstborn Son and wrapped Him in cloths and laid Him in a manger.”

— Luke 2:7

Matthew records the danger surrounding Him:

“Herod… sent and killed all the male children in Bethlehem.”

— Matthew 2:16

Christ’s earliest hours unfolded in a world that frequently discarded children like Him. He entered human life without insulation. Nothing shielded Him from the realities of empire.

Paul later writes:

“Though He was in the form of God… He emptied Himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.”

— Philippians 2:6–7

And then he gives the line that gathers the entire story:

“When the fullness of time had come, God sent forth His Son, born of a woman.”

— Galatians 4:4

God did not avoid vulnerability.

He entered it.

What He Came to Do

When John the Baptist’s followers asked Jesus whether He was truly the One, He answered by naming what His presence was restoring:

“The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news preached to them.”

— Matthew 11:5

Instead of pointing to spectacle or strength, He directed their attention to the people whose lives had been restored.

Why Rio Returned to Me During Advent

Watching the torch rise in 2016, I sensed the quiet reversal of the ideology that shaped both Rome and the Third Reich. The meaning of the ritual had shifted. A ceremony crafted to elevate a flawless ideal was now being carried by someone who contradicted that ideal simply by being present. The reaction of the stadium revealed a different vision of humanity — one that Advent has always pointed toward.

Luke tells us that God’s announcement of Christ’s birth came to shepherds in the night:

“Fear not, for behold, I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people.”

— Luke 2:10

Isaiah describes the Messiah in terms that move toward vulnerability:

“He will not break a bruised reed and a smoldering wick He will not snuff out..”

— Isaiah 42:3 (also quoted in Matthew 12:20)

Scripture consistently reveals God turning toward what the world dismisses.

What Advent Reveals

The Child in Bethlehem does not arrive in the form admired by Rome or celebrated in Berlin. He comes in the way God has always chosen to work — through the overlooked, the fragile, and the unexpected. His life becomes the place where God repairs what empire cannot.

That night in Rio made this clearer for me. The flame rising in the hands of someone the early Olympic ideal never intended to honor became a small icon of another kingdom — one that does not measure value by perfection or strength, but by the worth God gives to every human life.

Advent invites us to dwell in that difference.

A companion podcast is attached below.

Miriam and Daniel talk through the Berlin–Bethlehem–Brazil reflection and explore some of the ideas in a more conversational way. Feel free to listen as you go.

Thank you for the history lesson - it always ends up being His story!

You reminded me again why I love Special Olympics. It gives everyone a chance to feel the delight God has for each one of us. In a society that was shunning and making fun of people like my daughter, this organization emerged to counter that same lie with the truth that all life matters, especially the weak and vulnerable, and can be protected and celebrated as lavishly as it is by God.

The athlete motto: “Let me win, but if I do not win, let me be brave in the attempt.”

My 23 year old daughter doesn’t even know what that means and still can’t remember her gymnastics routines, but she does all her practices and events with such joy and delight that it makes everyone around her glad to be there. It’s God’s picture of how we were meant to live and work and relate to one another.

Thank you, Jesus, for coming to show us what it’s like to be truly human and for inspiring your people to create a better way in this world!

Thank you very much for sharing Jean. So grateful for this profoundly beautiful comment.