Forgotten Footsteps: The Gospel’s Long Journey East

Ancient Roots, Living Faith: The Forgotten Story of Christianity in the East

“Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of His saints.” (Psalm 116:15)

When we hear of visions of Jesus across the Middle East today,

we might imagine something new happening—a sudden spark in a dark land. But this region has been deeply shaped by the Gospel for millennia. The story of God’s kingdom here is not new; it is ancient, rich, and soaked in prayer and sacrifice.

The Persian Thread in Scripture

Long before the Church was born, the Persian Empire played a significant role in God’s story.

Aramaic (Syriac) was the imperial language of Persia for centuries, a language spoken across the Near East from Babylon to Jerusalem to Susa. Parts of the Old Testament—including Daniel, Ezra, and portions of Esther—were written in this very language, the language Jesus Himself later spoke.

The Last Word of the Jewish Scriptures

In the Hebrew ordering of the Scriptures, 2 Chronicles 36:23 is the final verse of the Bible. Its last word is עֲלֹה (ʿālôh), meaning “go up, ascend, rise up.” The Tanakh closes not with a curse or final judgment, but with an open invitation: return, rise, and go up to Jerusalem to rebuild the house of the Lord.

Some rabbis have reflected on this contrast: the Christian Old Testament ends with Malachi’s warning of “a curse,” and even the New Testament closes in Revelation with a solemn warning about prophecy. Yet the Jewish Scriptures end with a pilgrim word, a call that is not finality but movement toward God’s presence.

The last sound of the Hebrew Bible is a journeying word—a divine summons upward, into hope, into restoration, toward the place where God promises to dwell among His people once more.

2 Chronicles 36:22–23 records the decree of Cyrus:

22 Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the Lord by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled, the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia, so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing:

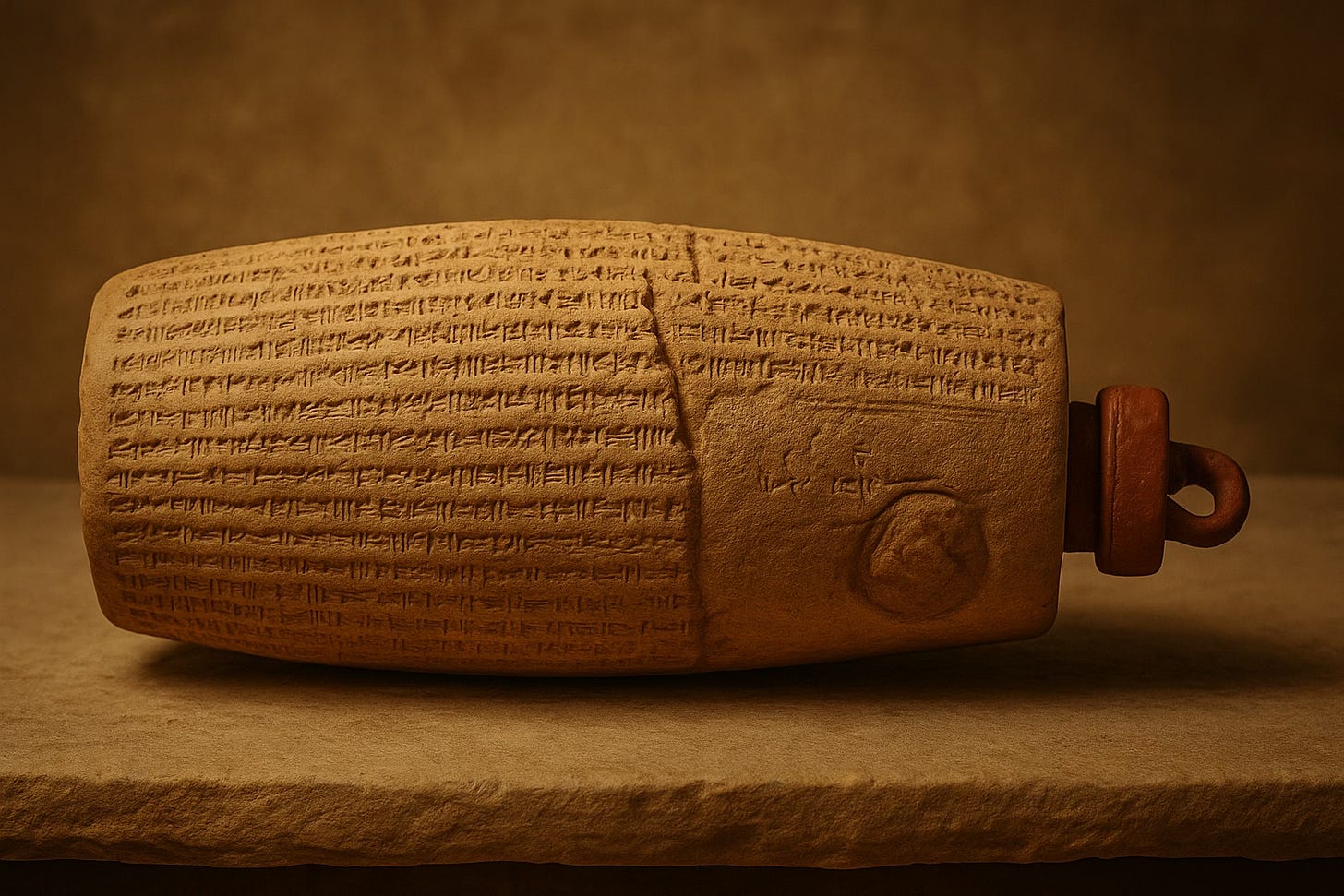

23 “Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, ‘The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him. Let him go up.’”This is a depiction of the Cyrus Cylinder, a famous ancient artifact from the 6th century BC, attributed to King Cyrus the Great of Persia. It is inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform and records Cyrus's conquest of Babylon (539 BC) and his policies of repatriation and religious tolerance. Many biblical scholars connect the decree mentioned on the cylinder to the events recorded in 2 Chronicles 36:22–23 and Ezra 1:1–4, where Cyrus permits the Jewish people to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. It’s often regarded as one of the earliest known declarations of religious freedom.

In every generation, even under persecution, there have been Persians who loved Jesus, from the earliest converts in Acts 2 (“Parthians, Medes, and Elamites”) to today’s courageous house church leaders.

A Faith that Went East

The Gospel did not only move west toward Rome. It traveled east along the Persian trade routes, carried by merchants, missionaries, and translators.

The Bible was translated early into Syriac (Aramaic), a dialect close to what Jesus spoke, and spread rapidly in Persia and Mesopotamia.

Armenia became the first nation to officially embrace Christianity in the early 4th century, long before most of Europe.

Monasteries and schools flourished across Persia, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, creating vast networks of learning and prayer.

Missionaries journeyed along the Silk Road into India and even reached China during the Han dynasty, centuries before Europe had widespread access to the Scriptures. By the 7th century, Nestorian stele inscriptions in Xi’an recorded the thriving Christian presence there.

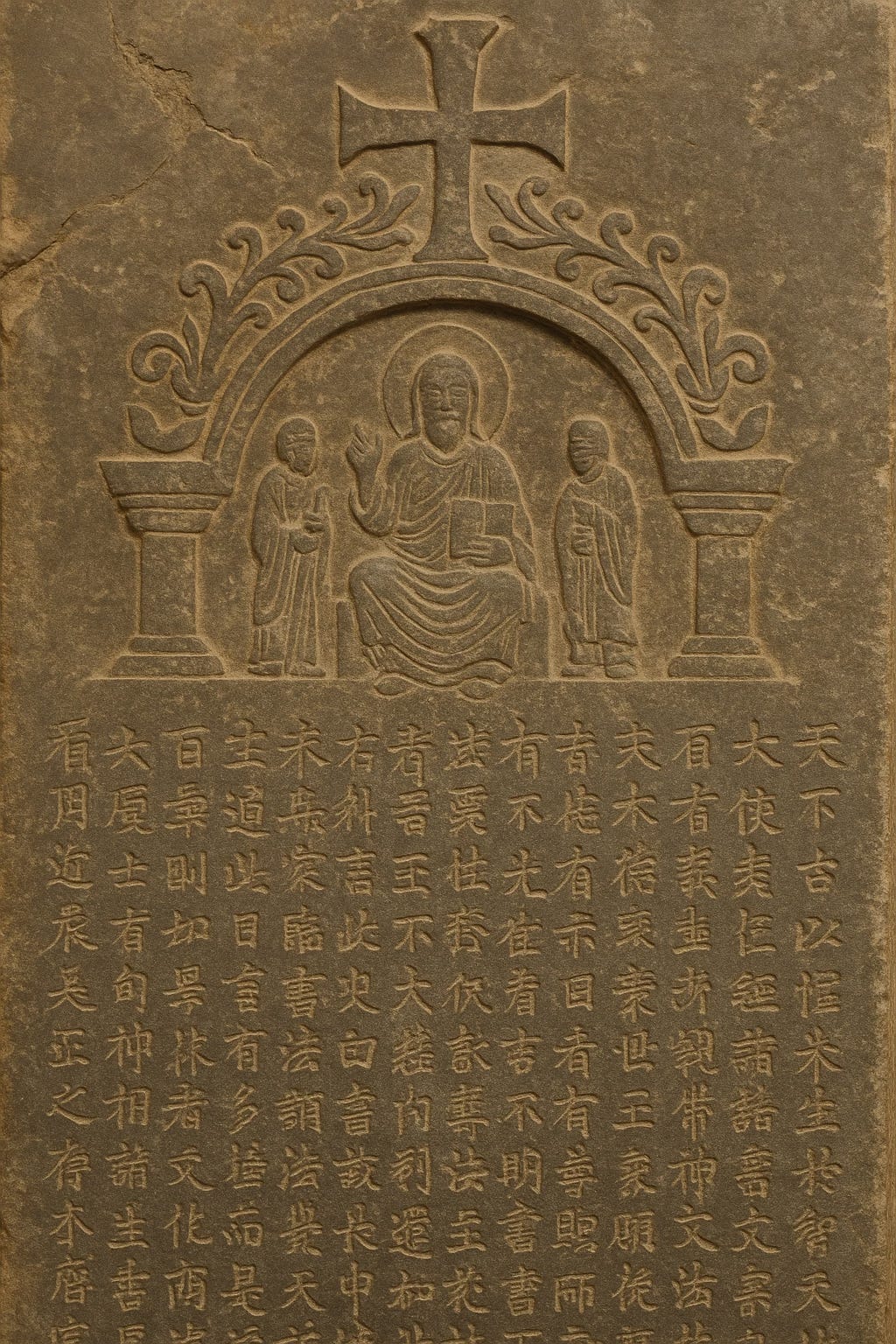

The Nestorian Stele, also known as the Xi'an Stele, dates to 781 AD (Tang Dynasty, China).

It commemorates nearly 150 years of Christian presence in China, brought by missionaries of the Church of the East (often called "Nestorian Christians"), who first arrived around 635 AD. The stele is written in both Chinese and Syriacand describes Christian teachings, the establishment of churches, and the support they received from the Tang emperors.

By the 7th century, Christian communities were so well established in China that the Nestorian Stele was erected in Xi’an in 781 AD (Tang Dynasty), commemorating nearly 150 years of Christian presence. Written in both Chinese and Syriac, it describes the teachings of Jesus, the establishment of churches, and the support they received from Tang emperors.

Historians like Philip Jenkins remind us that there were periods when more churches, monasteries, and believers existed east of Jerusalem than in all of Europe.

The Long History of Translation: Before Luther

When Martin Luther translated the Bible into German (New Testament in 1522, full Bible in 1534), it changed the face of Christianity in Western Europe, breaking Latin’s monopoly (the Vulgate) and giving ordinary believers access to Scripture. But Luther was not the first.

Centuries earlier, the Bible had been translated into many tongues:

Syriac (Peshitta) – 2nd century, the language of much of the early Eastern church.

Coptic – 3rd–4th century, for Egyptian Christians.

Ge’ez (Ethiopic) – 4th–5th century, foundational for Ethiopian faith.

Gothic – 4th century, Bishop Wulfila’s translation for the Goths.

Armenian – 5th century, following the creation of an entire alphabet to render Scripture.

Chinese – by the 7th–8th century, Nestorian missionaries from Persia brought biblical texts and concepts eastward along the Silk Road, translating them for Chinese audiences.

Some scholars have suggested that traces of Genesis may even echo in the ancient Chinese script. Characters like 船 (chuán), meaning boat, are formed from symbols for eight people in a vessel—reminiscent of Noah’s ark. 義 (yì), meaning righteousness, depicts a person under a lamb, evoking the image of atonement. 禁 (jìn), to forbid, combines the elements two trees and divine command, recalling Eden’s story. While linguists debate whether these links are coincidental or influenced by early Christian teaching, it is possible that Persian missionaries traveling the Silk Road used such existing symbols—or helped shape them conceptually—to express biblical truths in a language and culture far from Jerusalem. (C.H. Kang & Ethel R. Nelson, The Discovery of Genesis in Chinese Characters, Concordia Publishing, 1979.)

Long before Europe’s Reformation, the Word of God had already crossed languages, deserts, and empires—fulfilling the promise that every tribe and tongue would hear.

The Path of Scripture into India: The Mar Thoma Church

Tradition holds that St. Thomas the Apostle landed on the Malabar Coast (modern Kerala) in AD 52, preaching first among Jewish settlers in Cranganore (Malankara) before establishing seven early churches across Kerala. By AD 600, a well-rooted Thomas Christian community existed, using Syriac liturgy connected to the Church of the East.

Two major waves of Syrian Christian migrants from Persia arrived in AD 345 and AD 825, strengthening these communities with clergy, scholars, and new manuscripts of Scripture. Archaeological evidence—stone crosses, copper plates, and church ruins—attests to monasteries and thriving Christian settlements along India’s southwest coast from the early centuries of the faith.

Though Portuguese colonizers later attempted to impose Latin rites (from 1498 onward), the community resisted foreign control through the Coonan Cross Oath (1653) and reestablished apostolic leadership with Mar Thoma I (1665). The Mar Thoma Syrian Church continues today, a living witness to one of the earliest missions of the Gospel beyond Jerusalem.

A Land Marked by Martyrs

For almost a thousand years, this region was alive with faith—its soil marked by the prayers, songs, and blood of countless martyrs who followed Christ.

Even during the Islamic Golden Age, many of the translators who preserved Greek philosophy, medicine, and science into Arabic and Syriac were Christians. Their scholarship and faith shaped civilizations, leaving a quiet but enduring witness.

These lands are not forgotten by the Lord. He has loved these peoples for millennia, and He has walked among them long before modern mission efforts began.

Ancient Seeds, New Growth

So when we hear that revival is stirring today—that Jesus is appearing in dreams and visions, that churches are rising again in Persia, Armenia, Turkey, and beyond—we can remember:

This is not a new work. It is the Lord bringing ancient seeds to life, planted long ago by apostles, saints, and martyrs who carried His name across deserts, mountains, and empires.

The blood of the martyrs still cries out from the ground, and God’s promise still stands:

“The earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord” (Habakkuk 2:14).

A Prayer for These Lands

Lord Jesus,

We honor the ancient paths where Your people walked, prayed, and gave their lives for You.

We thank You for the kings of Persia who once honored Your name, for Daniel and Esther who shone like light in foreign courts, for early apostles who carried the Gospel eastward, and for Armenians, Persians, Syriac believers, Thomas Christians, and missionaries who filled these lands with worship for centuries.

We thank You for every martyr whose blood watered the soil of Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, India, and China.

We pray for these regions today—let the old prayers bear new fruit, let the old wells be reopened, let the ancient paths lead many home to You.

Show Your mercy to these peoples whom You have loved for millennia.

Breathe life again into Your church along the Silk Road, and let Your glory rise in these nations once more.

Amen.

Further Reading

Philip Jenkins – The Lost History of Christianity (HarperOne, 2009)

Wilhelm Baum & Dietmar W. Winkler – The Church of the East: A Concise History (Routledge, 2003)

Sebastian Brock – The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage (Gorgias Press, 2001)

Biblical Archaeology Society – The Syriac World: Forgotten Christianity